The Rule of 40 is Dead… Long Live the Rule!

At the end of 2023, TechCrunch ran a very influential piece that got forwarded around the SaaS world in a flash. The jolting punchline? The “Rule of 40 … is dead wrong,” proclaimed Bessemer’s Byron Deeter and Sam Bondy.

Of course, outside of the tiny world of pre-IPO, venture-backed SaaS, the Rule of 40 was always misleading. But when Deeter declared it dead, the industry sat up and listened. At SaaS Capital, we had three main reactions.

The Rule of 40 and its Discontents

Only a sliver of the population of SaaS companies get “40” when adding their growth rate plus profitability percentage (in fact, the “Rule of Zero” is more useful to separate the thriving from the struggling).

But that didn’t stop widespread adoption of Brad Feld’s 2015-era “Rule,” which was memorable, simple to calculate, and made analysts sound smart to folks who’d never heard of it. If 40 wasn’t optimistic enough for you, you could even get consultants to promise to help you reach a rule of “50s, 60s, or even 80s.”

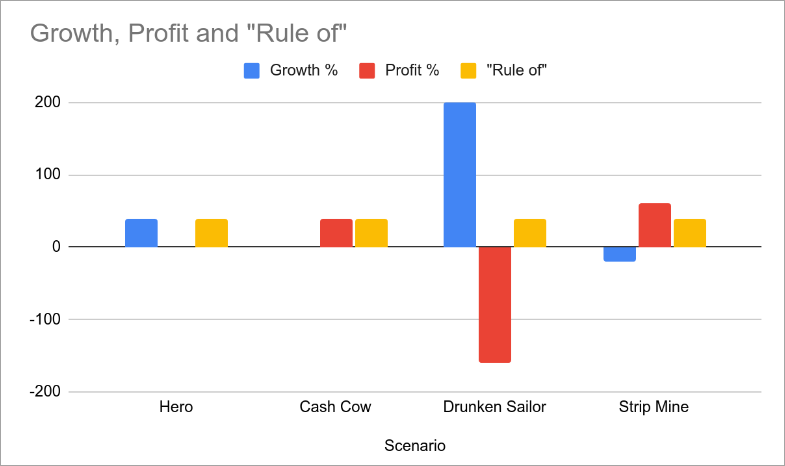

The rule’s major flaw is that a company achieving a growth rate plus profitability ratio, or GP Ratio, of “40” through 40% growth and breakeven is fundamentally a very different company than one also achieving “40,” but through 40% free cash flow and 0% growth.

You can see this by taking the extremes of a company growing 200% per year but burning 160% of revenue to get there, versus a company with 60% profitability that’s shrinking 20% per year. All four scenarios are very different businesses and they are not equally good. (The last two examples may not even be good at all, depending on other factors!)

The chart below might help visualize how different a company’s trajectory could be while still being “Rule of 40”. Which one would you rather own?

To Every Metric, There is a Season

But even if it’s fair to say that growth is gold and profitability is silver – it’s not always true that they’re preferred in quite the same way.

For much of the history of the SaaS industry, capital was relatively easy to get. Once SaaS became the de facto standard way to deliver software, venture capital (VC) flowed in readily and interest rates were low. As a result, profitability, particularly for smaller, private companies, was de-emphasized and growth, in turn, was the focus.

Our 2022 analysis of valuation factors, which led to our valuation methodology and white paper, found that profitability wasn’t even a useful input – at least at that time. Growth and retention were so much more important that they completely overshadowed profitability (as statistical predictors, at least).

But in a time when equity funding is more scarce, and when the cost of debt goes up – a time like, say, 2023 to present – you would expect that profitability would become more important. Indeed, that’s exactly what’s happened, and we will be publishing some research shortly showing that public markets have flip-flopped. In 2024, silver still isn’t gold, but it shines a little more like gold today than before, it seems.

A Time to Sow, a Time to Reap

While public markets are signaling a preference for profitability, relative to prior years, there is still an absolute preference for growth. And that’s the case in public markets, where you would expect a much more mature market that is already penetrated well.

The change in public market appetites doesn’t fundamentally change the math for private SaaS companies, however. If you’re below $100 M in annual recurring revenue (ARR), you should have so much “headroom” to grow that shifting entirely to a profitable annuity model would be a huge strategic mistake (but see our practical recommendations at bottom).

Private SaaS companies should try to burn less money as they continue to grow, in keeping with the relatively less accommodating market for raising money. That is, they should adjust their “profitability” upward. But they should not be trying to be profitable in the sense of retaining positive cash flow each year!

A small private SaaS company (except in tiny niche markets) should never be in “harvest mode” of producing cash flow. There’s simply too much opportunity out there, and the techniques for going to market are accessible enough, that harvesting while well under $100 M in ARR is an unforced error (or a sign that your business might not truly be a viable B2B SaaS company).

Practical Advice

Given the above, we think the actual guiding rule in 2024 should be this:

For companies at least 2 years away from an exit transaction, grow as sustainably fast as your expected access to capital will allow you in your chosen market, and burn as much cash as you can access. Nobody can predict the relative growth vs. profitability weighting for acquirers 2 years from now, but in the long term, growth will always be golden. Don’t worry about spending too fast: the capital markets in 2024 will likely be self-constraining in the amount of cash you can access.

For companies with an exit horizon within 2 years, get to breakeven to own your destiny. If you can continue to grow well at or near breakeven, you will have an exceptional opportunity to stand out among acquisition targets. Even if growth slows, you will have the luxury of time and negotiating leverage. (Many of our borrowers in this situation use a debt facility to allow them to fearlessly manage to “approximately” breakeven, without worrying about running out of cash month to month; this provides an essentially indefinitely long runway.)

Under no circumstances should you intentionally manage a sub-$100M B2B SaaS company to generate significant annual profit, unless your plan is to quasi-retire and “milk” it dry. Even if you plan to leave a wholly-owned SaaS company to your heirs, you should be emphasizing growth in order to create the most value and the best options for them. A significant net profit at a sub-scale company in this sector is an adverse signal to an acquirer that you’re stuck in a niche without attractive reinvestment opportunities beyond your company’s money-market account.

![]()