How to Do Each Qualitative Data Coding Type (All Steps)

Qualitative data coding is the process of organizing all the descriptive data you collect during a research project.

It has nothing to do with computer programming, and everything to do with sorting and categorizing non-numerical data.

It’s actually pretty simple.

We like how qualitative data coding is described in the book Qualitative Research Using R: A Systematic Approach: “Coding assigns a meaning to a small body of text (e.g., a specific word or lexical item, a sentence, a phrase or paragraph) using a label (usually one to a few words)….that best represents the text.”

In short, it’s all about finding and organizing the insights in your qualitative data.

There are 4 different types of qualitative data coding. (Not sure what we mean by qualitative data? Check out our guide to qualitative vs. quantitative data for a quick overview.) We’ll define each one and then walk you through how to do them, step by step.

1. Deductive Coding

Deductive coding is a top-down technique where you create a set of codes that correspond to the main themes in your research.

Say you’re working with a bunch of interview transcripts or open-ended survey responses. You need a way to:

- Identify topics that are central to your research

- Quickly find those topics in your qualitative data

Deductive coding helps you do just that. And it’s fairly simple to do. All you have to do is create a set of codes, or phrases, that correspond to the themes you’re exploring as part of your project. If you’re studying people’s experiences with healthcare, you might have codes like “access to care,” “bedside manner,” or “pain level.”

As you go through your data, you’ll tag sections of text with these codes.

With deductive codes, you’re basically creating a map of your data that highlights the parts most relevant to your research. This makes it much easier to see patterns and draw meaningful conclusions from the information.

How to Do Deductive Coding

Your first step will be to figure out which research questions or themes you want to explore in your data. Let’s circle back to the healthcare example. You’re studying how a medical provider’s bedside manner impacts a patient’s pain and perception of quality care.

You develop a list of deductive codes that correspond to these themes:

- Bedside manner: Tag data that talks about how the medical provider interacts with patients. How’s their tone? What about their empathy, attentiveness, and communication style?

- Patient pain perception: With this code, tag segments where patients talk about their pain—and how their provider helps manage it (or not).

- Quality of care perception: Apply this code to any mention of how patients perceive their overall quality of care from the provider(s).

- Provider communication: Tag sections of the qualitative data that focus on how well the provider conveys information, listens to the patient, and explains treatment plans.

- Emotional response: Does the patient feel anxious? Comforted? Respected? Dismissed? With this code, you’ll tag all emotional reactions to and during care.

- Pain management strategies: Tag any sections of the data that mentions methods or strategies the provider uses to manage a patient’s pain.

- Trust in provider: Tag words or sections that hint at the patient’s trust level with their provider.

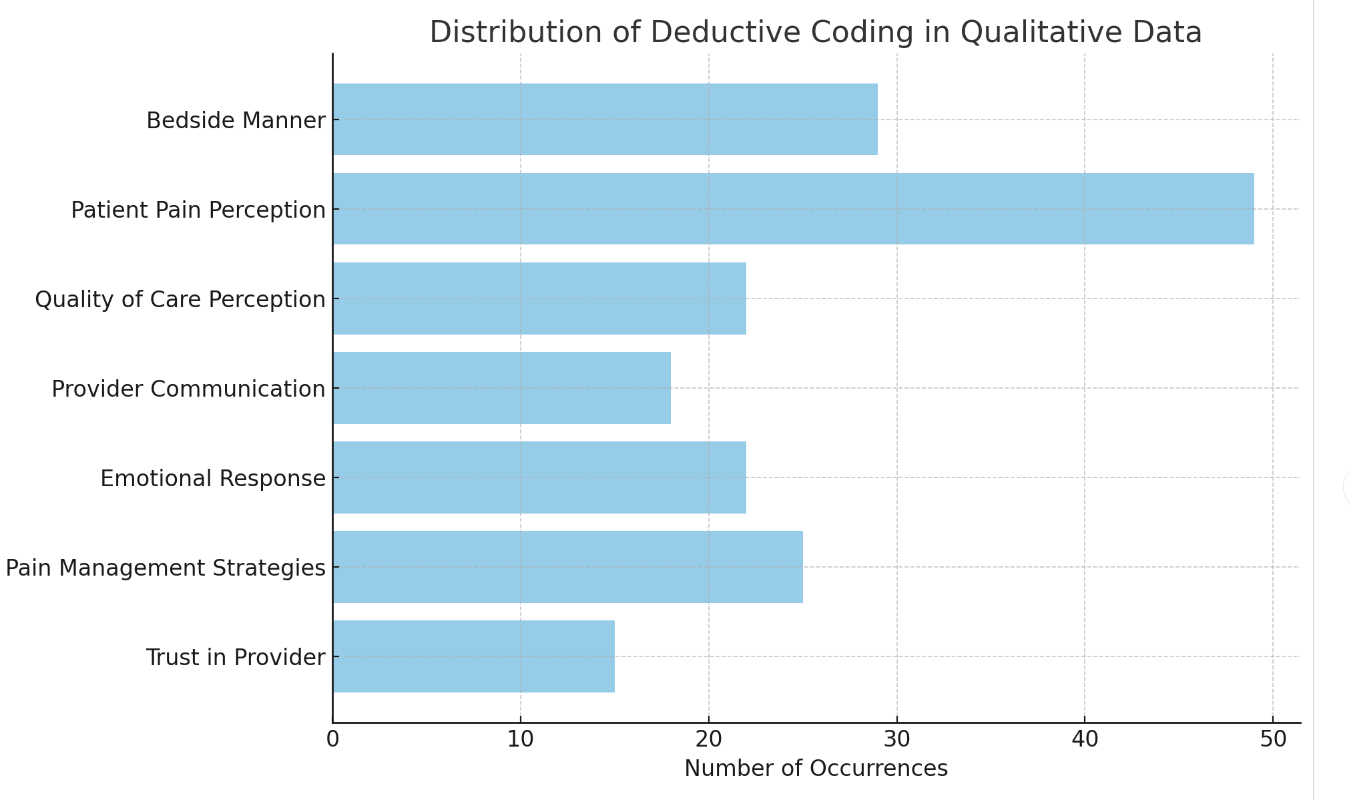

Once you’ve tagged all the data, you can put it in a chart or graph for easy visualization. Here’s what our qualitative patient-doctor data might look like in a chart or graph format.

2. Inductive Coding

With inductive coding, you let codes arise from your data instead of identifying them beforehand. Unlike deductive coding, the inductive method works from the ground up.

Instead of making a list of codes like you do in deductive coding, you’ll read through your qualitative data and write down potential code phrases as they emerge.

Researchers use inductive coding when they want to analyze a set of qualitative data without coming to it with any biases.

Here’s an example of how to use it.

How to Do Inductive Coding

We’ll imagine we’re looking at the other side of the doctor-patient relationship—in other words, how doctors and other medical providers feel about their patients.

This interview is a real conversation between a London General Practitioner, Iona Heath, and Ray Moynihan, host of the health podcast, “The Recommended Dose.”

To do inductive coding, you’ll jot down phrases or words that come to mind as you read the transcript. We came away with a few:

- Forging connections and relationships: Tag qualitative data that pertains to the connections medical providers do (or don’t) form with their patients, and how that affects care.

- Patient difficulty: Tag each instance in which a provider says a patient is difficult.

- Emotional response: Tag pieces of text that discuss a provider’s emotional response to a difficult or easy patient.

As you continue reading transcripts, you can use these codes to tag data. But you can also stay open to the possibility of new codes that emerge as you read.

Once you’ve gathered, coded, and tagged all the data, you can organize it into a visually appealing format. You’ll be left with a trove of organic data that tells you what it’s about, rather than the other way around.

Inductive coding is also called open coding, especially when you’re using the grounded theory approach in analyzing qualitative data. Grounded theory basically means approaching data with no preconceived notions and allowing the data to inform the researcher. You can learn more about this analysis method in our guide to qualitative data analysis methods.

In grounded theory, open coding is the first of a three-part coding process that includes axial and selective coding.

Let’s dive into those two coding types next.

3. Axial Coding

In axial coding, you take the categories identified during open coding and find relationships between them.

Since it’s part of grounded theory, axial coding does not require you to come in with preconceived ideas about how data points will (or won’t) relate to each other.

But you can technically also use axial coding after doing deductive coding—the type of coding that has you approach qualitative data with predetermined, top-down research topics.

The purpose of axial coding is simply to find connections between different categories of your qualitative data.

How to Do Axial Coding

Going back to our medical provider research example, let’s imagine we’ve done some open coding to break down our data and identify key themes.

Our next step is to use axial coding to create axes (categories) and supporting codes (sub-categories) with these themes.

In our inductive/open coding process, we pinpointed three open codes:

- Forging connections and relationships

- Patient difficulty

- Emotional response

To conduct axial coding, we’ll look for the subcategories, or supporting codes, for each of these inductive codes.

This means digging through our tags—the sections of text we tagged according to our inductive codes—and identifying the causes and consequences of each code.

In our first open code, forging connections and relationships, we identify key factors that come into play:

- Causes: When physicians make a personal effort to understand the backgrounds of their patients, listen to their concerns, and express empathy, this strengthens the patient-doctor relationship.

- Consequences: As a result of these improved connections, the provider and patient enjoy improved trust, increased rapport, higher accuracy in diagnosis and treatment, and better compliance with care plans.

Now let’s look at the second code, patient difficulty:

- Causes: Patient difficulty arises due to three key reasons, including communication barriers, complex medical histories, and non-compliance with treatment recommendations.

- Consequences: As a result, providers may feel frustrated and as though they are spending too much time consulting with—and allocating resources for—their challenging patient. Because of this, there’s a chance of increased misdiagnosis or even ineffective treatment.

Finally, here’s what we identify with the third code, emotional response:

- Causes: Doctors feel an increased emotional response when they succeed in treating complicated cases, when they see challenging patients frequently, and when they feel burned out on medicine—or stressed about things in their personal lives.

- Consequences: As a result, doctors may feel fulfilled when they have a successful patient outcome, emotionally exhausted or burned out, or feel a mixed, emotional impact on their job performance.

Now that we’ve made these connections from studying our tagged qualitative data, we can turn it into a table that makes it easy to study—and use for our next steps.

4. Selective Coding

Selective coding focuses on developing a core theme or theory from everything you’ve discovered in open and axial coding.

Because you’ve already done the lion’s share of the coding work at this point, selective coding is pretty easy.

How to Do Selective Coding

The first step to conducting selective coding is to review your axial coding chart. What are the relationships between the categories? Is there a single category that ties everything together? One that’s central to the data?

In our patient-doctor example, let’s say we decide that doctor-patient relationships is our core category.

Why? Because it ties all the subcategories together. It’s the overarching theme, as identified by our qualitative data, that influences how doctors feel about their patients.

Now we need to look at how each subcategory—forging connections and relationships, patient difficulty, and emotional response—relates to the core category.

We might realize that forging connections and relationships impacts the quality of doctor-patient relationships. And this, in turn, affects patient difficulty and emotional response.

From here, we can piece together our theory. The theory might go something like this: “Strong doctor-patient relationships are built through empathy and communication. These relationships help elicit positive emotional responses from healthcare providers. Positive emotional responses, in turn, make it easier for physicians to work with difficult patients.”

Now, go back to your data and test the theory against it. Does it fit? If so, that’s great. You can now use the data to inform your next steps, whether that’s improving patient-doctor relationships using a cool new app or implementing training that helps doctors understand their patients’ needs.

If not, it’s time to refine your theory until it does fit the qualitative data.